The Invisible Hand of Human Dharma

Eastern Philosophy Explains The Invisible Hand

The concept that best matches the invisible hand is simply “the aspects of human nature which maintain social order”.

The apprehension of economists to come to such a conclusion is understandable as Western philosophy has not developed such a concept extensively.

Eastern philosophy, on the other hand, has observed natural processes for thousands of years and has formalized it under the term dharma. Dharma is defined as the nature of existing phenomena that supports and holds the universe together. The dharma that applies to human society is called societal dharma (varna dharma) and is defined as the whole set of behaviors necessary for the maintenance of the natural order of society. According to the Mahabharata (Ganguli, n.d.):

Dharma protects and preserves the people. So it is the conclusion of the Pandits that what maintains is Dharma.

Karna Parva, Chap. 69

Each individual behavior, which makes up the whole, is called personal dharma (svadharma), or one’s own nature and duty within a bigger order.

Societal and personal dharma thus fall under the broader term called human dharma which is the nature and duty of humans, as opposed to animal and physical dharma or the nature of animals and physical forces.

According to the Bhagavad Gita, it is essential that each person acts according to his or her dharma (Easwaran, 2007):

It is better to strive in one’s own dharma than to succeed in the dharma of another. Nothing is ever lost in following one’s own dharma, but competition in another’s dharma breeds fear and insecurity.

Bhagavad Gita, Chapter 3:35

A similar idea was echoed by Confucius:

Confucius had said..“Let the ruler rule as he should and the minister be a minister as he should..” If everyone performed his role, the social order would be sustained.

Fairbank & Goldman, 2006, p. 52

| Occupation | Indian | Chinese | Japanese |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unskilled | Laborer | Shudra | 农 Nong |

| Skilled Laborer | Shudra | 工 Gong | Farmer |

| Warrior / Leader | Ksattriya | 士 Shi | Warrior |

| Intellectual / Creative | Brahmin | 士 Shi | Artisans |

| Merchant | Vaishya | 商 Shang | Merchants |

The closest English word for personal dharma is “personal-interest” and so, butchers must act on the interest of butchers (or the dharma of butchers), while brewers must act on theirs (the dharma of brewers). This will naturally and invisibly lead to societal dharma or the maintenance of society through the efficiency afforded by the division of labor, leading to better goods and services acquired through trade:

This division of labour..is not originally the effect of any human wisdom..It is the..consequence of a certain propensity in human nature..to..exchange one thing for another..It is common to all men..

Adam Smith

WN, Book 1, Chap. 2, Pars. 1 & 2, emphasis added

How the Invisible Hand Balances Employment Between Two Towns

Societal dharma naturally balances the amount of productive hands, by attracting self-interest (svadharma) in a location through the demand of the society which, in the end, gives back ordinary profits, or the value that the society can collectively give back:

The mercantile stock of every country naturally courts in this manner the near, and shuns the distant employment; naturally courts the employment in which the returns are frequent, and shuns that in which they are distant and slow; naturally courts the employment in which it can maintain the greatest quantity of productive labour in the country to which it belongs, or in which its owner resides, and shuns that in which it can maintain there the smallest quantity.

It naturally courts the employment which in ordinary cases is most advantageous, and shuns that which in ordinary cases is least advantageous to that country. But if in any of those distant employments, which in ordinary cases are less advantageous to the country, the profit should happen to rise somewhat higher than what is sufficient to balance the natural preference which is given to nearer employments, this superiority of profit will draw stock from those nearer employments, till the profits of all return to their proper level.

This superiority of profit, however, is a proof that, in the actual circumstances of the society, those distant employments are somewhat under-stocked in proportion to other employments, and that the stock of the society is not distributed in the properest manner among all the different employments carried on in it.

It is a proof that something is either bought cheaper or sold dearer than it ought to be, and that some particular class of citizens is more or less oppressed either by paying more or by getting less than what is suitable to that equality which ought to take place, and which naturally does take place among all the different classes of them..But if the profits of those who deal in such goods are above their proper level, those goods will be sold dearer than they ought to be, or somewhat above their natural price, and all those engaged in the nearer employments will be more or less oppressed by this high price.

Their interest, therefore, in this case requires that some stock should be withdrawn from those nearer employments, and turned towards that distant one, in order to reduce its profits to their proper level, and the price of the goods which it deals in to their natural price.

In this extraordinary case, the public interest requires that some stock should be withdrawn from those employments which in ordinary cases are more advantageous, and turned towards one which in ordinary cases is less advantageous to the public; and in this extraordinary case the natural interests and inclinations of men coincide as exactly with the public interest as in all other ordinary cases, and lead them to withdraw stock from the near, and to turn it towards the distant employment.

It is thus that the private interests and passions of individuals naturally dispose them to turn their stocks towards the employments which in ordinary cases are most advantageous to the society. But if from this natural preference they should turn too much of it towards those employments, the fall of profit in them and the rise of it in all others immediately dispose them to alter this faulty distribution.

Book 4, Chapter 7, Par 73, emphasis added

To illustrate the balancing of employment, let us say there are two nearly-identical towns: Red town and Blue town.

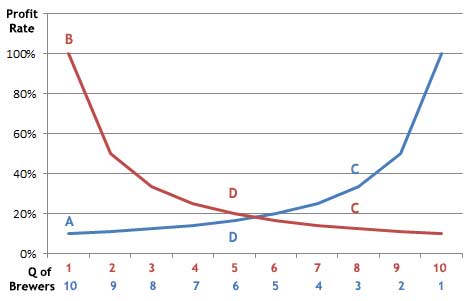

The only difference is that Blue town has ten competing brewers sharing 100% of the profits from sales of beer in Blue town or around 10% share per brewer (Point A), while Red town has only one brewer to profit 100% from its beer demand (Point B).

Soon or later, the brewers in Blue town will be attracted to the high profits in Red town.

If seven Blue town brewers move to Red town, the profit rate in Red town will fall to 12.5%, while Blue town’s will rise to 33% (Points C).

The higher profits back in Blue town will gradually prompt brewers to return to Blue town until the profit rates are roughly equal (Point D).

In a mercantile system however, the invisible hand is replaced with the mercantile and corporation spirit.

Using the same example, a mercantile Blue town brewer will seek to monopolize profits to himself by creating intellectual property on brewing, eliminating all other brewers. He will then claim the profits of Red town by setting up a corporation to extend his person to Red town, something that is not naturally possible.

The efficient distribution of productive hands artificially existed in pre-colonial India and in the Song and early Ming dynasties of China (Fairbank & Goldman), and was known to Smith:

China has been long one of the richest..countries in the world. Marco Polo..describes its..industry..in the same terms..described..in the present..It had perhaps, even long before his time, acquired that full..riches which..its laws and institutions permits it to acquire. (WN, Book 1, Chap. 8, Par. 24)

Fairbank & Goldman, 2006, p. 52

However, the invisible hand in those empires was artificial because it was imposed by religion or tradition, and not by democracy:

The police must be as violent as that of Indostan or antient Egypt (where every man was bound by..religion to follow the occupation of his father..), which can..sink either the wages of labour or the profits of stock below their natural rate. The poverty of the lower ranks of people in China far surpasses that of the most beggarly nations in Europe.

Adam Smith

Chap. 7, Par. 31

Though not ideal, this artificial invisible hand prevented society from moving backwards:

China..though it may perhaps stand still, does not seem to go backwards. Its towns are no-where deserted by their inhabitants. The lands..are no-where neglected. The same..annual labour must therefore continue to be performed, and the funds.. maintaining it must not..be..diminished.

Adam Smith

Chap. 8, Par. 25

This artificial invisible hand raised productivity in order to provide for the natural needs of Chinese society. Smith, back in the 1700’s, accurately predicted that the inherent productive capacity of China and Japan would be able to reproduce foreign manufactures successfully:

A more extensive foreign trade, however, which to this great home (Chinese) market added the foreign market of all the rest of the world; especially if any considerable part of this trade was carried on in Chinese ships; could scarce fail to increase very much the manufactures of China, and to improve very much the productive powers of its manufacturing industry. By a more extensive navigation, the Chinese would naturally learn the art of using and constructing themselves all the different machines made use of in other countries, as well as the other improvements of art and industry which are practised in all the different parts of the world. Upon their present plan they have little opportunity except that of the Japanese.

Adam Smith

WN, Book 4, Chap. 9, Par. 41

The wealth of ancient China and India dwarfed those of Europe, until they were uprooted by war and European colonization to be replaced by Mercantilism. Adam Smith’s first description of the invisible hand in his earlier essay The History of Astronomy, is consistent with the Eastern belief that human dharma only affects humans while physical dharma only affects physics:

For it may be observed, that in all Polytheistic religions, among savages, as well as in the early ages of Heathen antiquity, it is the irregular events of nature only that are ascribed to the agency and power of their gods. Fire burns, and water refreshes; heavy bodies descend, and lighter substances fly upwards, by the necessity of their own nature; nor was the invisible hand of Jupiter ever apprehended to be employed in those matters.

Adam Smith

Section 3, emphasis added

While humans would naturally want to uplift society for our own sake, Mother Nature may want to destroy it through volcanic eruptions or sustain it through life-giving rain. As human dharma is different from the natural sciences or physical dharma, it observes its own sets of rules called morality, which was the focus of Smith’s book The Theory of Moral Sentiments, a book which he regarded as his greatest work:

..upon this is founded that.. distinction between justice and all..social virtues..that we feel..to be under a stricter obligation to act according to justice, than..to friendship..or generosity…We feel..that force may, with the utmost propriety..be made..to constrain us to observe the rules of the one, but not..the precepts of the other (TMS, Part 2, Sec. 2, Par. 5). But by acting according to..our moral faculties, we..pursue the most effectual means for promoting the happiness of mankind, and..to co-operate with the Deity.

Adam Smith

TMS, Part 3, Chap. 5, Par. 7

It is the deception of wealth and power which causes the corruption of moral sentiments:

This disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful, and to despise, or, at least, to neglect persons of poor and mean condition, though necessary both to establish and to maintain the distinction of ranks and the order of society, is, at the same time, the great and most universal cause of the corruption of our moral sentiments. That wealth and greatness are often regarded with the respect and admiration which are due only to wisdom and virtue; and that the contempt, of which vice and folly are the only proper objects, is often most unjustly bestowed upon poverty and weakness, has been the complaint of moralists in all ages.

Adam Smith

TMS, Part 1, Sec. 2, Chap. 3

Smith declares that the invisible hand, which is a part of a larger system, is from a higher being:

The administration of the great system of the universe, however, the care of the universal happiness of all rational and sensible beings, is the business of God and not of man.

Adam Smith

TMS, Part 6, Sec. 2, Par. 49

This is consistent with observations throughout history wherein morality and justice are often associated with gods, or one’s conscience. Whenever selfishness and injustice reach extremes in a society, people naturally react and cause change. As Capitalist dharma is based on the dogma of selfish-interest instead of human dharma, its “selfish hand” overpowers the invisible hand rendering it unable to spread value to society while creating various economic problems such as poverty, recessions, and negative externalities.