The Comet's Tail and Its Various Phenomena

Table of Contents

133. The Comet’s Tail and Its Various Phenomena

Comets exhibit a long, radiant tail, which gives them their name.

This tail is always seen on the side roughly opposite to the Sun. So, if the Earth is positioned in a straight line between the comet and the Sun, the tail appears to spread in all directions around the comet.

For instance, the comet of 1475 displayed a tail when it was first seen. By the end of its appearance, it trailed its tail behind it as it was in the opposite region of the sky.

This length of this tail depends on several factors:

- The size of the comet

Small comets have no tail. Large ones can appear very small when receding from our view.

- Location

All else being equal, the the tail appears longer the farther the Earth is from a straight line drawn from the comet to the Sun.

Sometimes, when the comet is hidden under the Sun’s rays, only the tip of its tail, resembling a fiery beam, is visible.

Lastly, the tail can sometimes be wider or narrower, straight or curved, and sometimes directly opposed to the Sun or not precisely so.

134. This Tail Depends a Certain Refraction

The comet’s tail is caused by a new type of refraction. I did not discuss this in Dioptrics because it is not observed in terrestrial bodies.

This refraction arises because air-aether globules are not all equal in size. Instead, they are:

- gradually smaller from the orbit of Saturn going into the Sun

- grdually larger from beyond the orbit of Saturn

Thus, the rays of light that are reflected by comets towards the Earth are transmitted from the larger of these particles to the smaller ones in straight lines.

They get refracted, deviating and scattering slightly to either side due to these smaller particles.

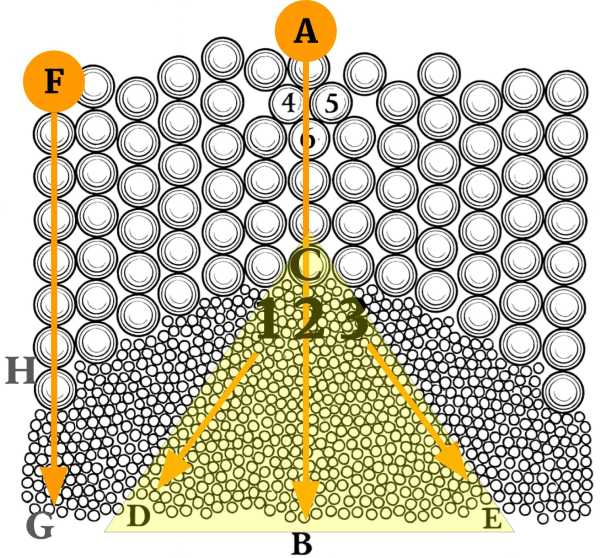

135. Explanation of This Refraction

Imagine fairly large balls resting on much smaller ones, all in continuous motion.

Ball A is pushed toward B.

This simultaneously pushes all the others that lie in that same direction, that is, all those along the straight line AB, communicating its action to them.

This transmitted action passes in a straight line from A to C. But only part of it continues straight from C to B.

The rest is diverted and spreads around toward D and E. For the ball C cannot push the small ball marked 2 towards B without also pushing the two others, 1 and 3, towards D and E.

By doing so, it also pushes all those lying within the triangle DCE.

This does not happen in the same way when ball A pushes balls 4 and 5 toward C.

Even though the action that pushes them seems to be diverted by these two balls toward D and E, it nonetheless passes entirely toward C.

This is:

- partly because balls

4and5are equally supported on both sides by those surrounding them.- They transmit the entire action to ball

6

- They transmit the entire action to ball

- partly because their continuous motion prevents the action from ever being received jointly by

4and5for any significant time

An action that diverts one large ball to one side is cancelled by another large ball that, through the same action, diverts it to the opposite side.

- And so the action always follows the same straight line.

But when ball C pushes the smaller balls 1, 2, and 3 toward B, its action cannot be transmitted entirely in the same straight line.

These smaller balls are in motion. Several of them always receive the action obliquely, diverting it simultaneously in various directions.

Therefore, although the main force—or the principal ray—of this action always passes in a straight line from C to B, it divides into an infinite number of weaker rays that spread toward D and E.

Similarly, if ball F is pushed toward G, its action travels in a straight line from F to H.

Once it arrives at H, it is transmitted to the small balls 7, 8, and 9, which divide it into multiple rays.

The main ray goes toward G, while the others are diverted toward D.

I assume the line HC which serves as the boundary between the large and small balls is a circle.

The rays of action must be diverted differently depending on how they strike this circle.

Thus, the action coming from A towards C:

- sends its principal ray towards

B - distributes the others equally to both sides,

DandEbecauseACmeets the circle at a right angle.

The action coming from F towards H also sends its principal ray towards H.

But since FH meets the circle at the most oblique angle possible, the other rays are diverted only towards one side—toward D.

- It spreads across the entire space between

GandB, becoming weaker the farther they deviate from the lineHG.

Finally, if FH does not strike the circle quite so obliquely, some of these rays are also diverted towards the opposite side.

However, the more oblique the incidence, the fewer such rays there are, and the weaker they become.